By Dr. Michelle Garnett and Professor Tony Attwood

A truly inclusive classroom would be one where everyone is welcome and celebrated, regardless of gender, age, ethnicity, socio-economic background, learning differences, language skills, motor ability, physical state, mental health status or neurotype. We are not there yet. This first article in a 2-part series on creating neurodiversity inclusive and affirming classrooms describes the journey, starting in the mid-nineteenth century with a vision for including students of all abilities within one classroom, to where we are now, and finally a vision for the future. We believe that by creating neurodiversity inclusive and affirming classrooms, the changes will benefit all students and teachers.

Where are we now and how did we get here?

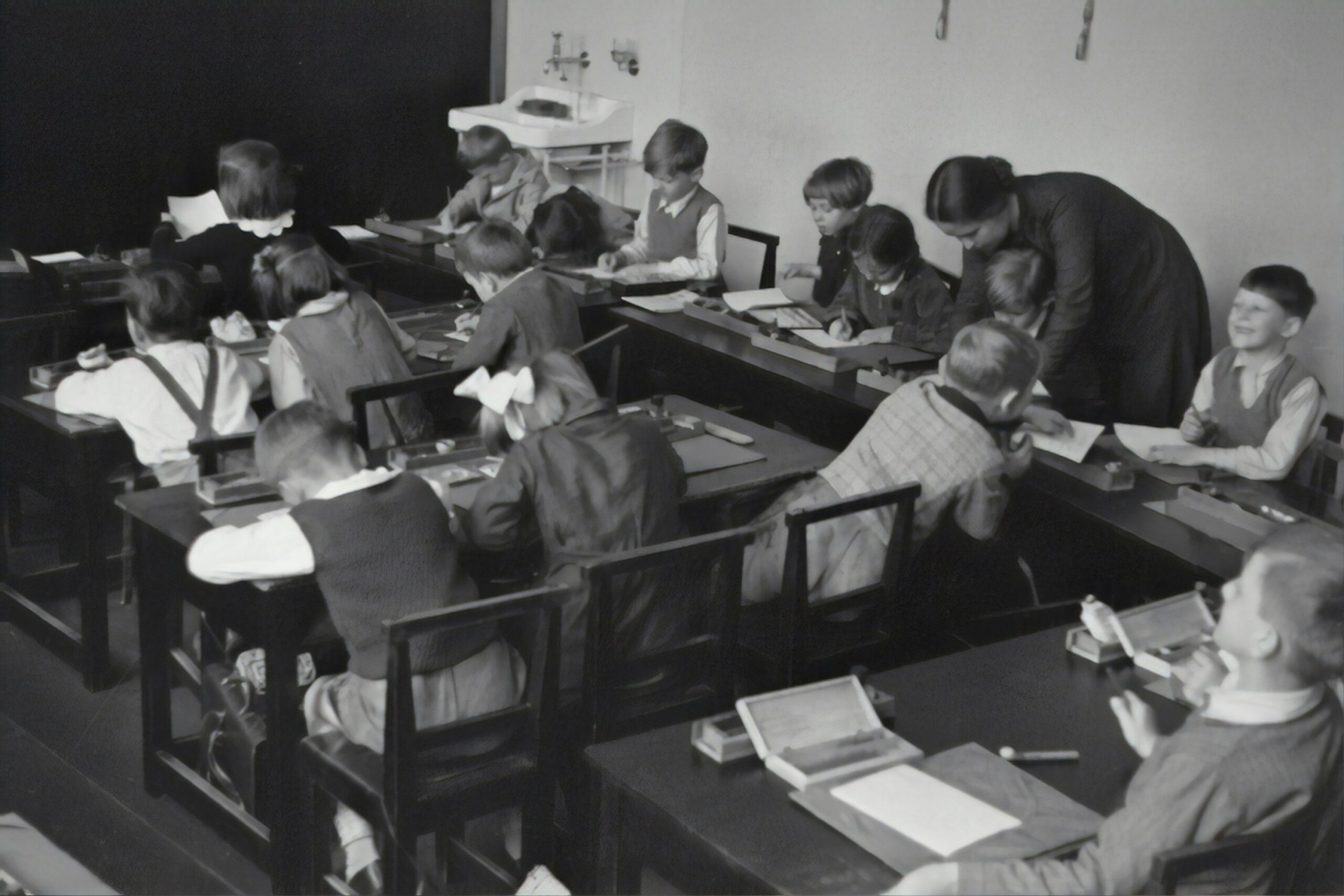

Prior to the 1950s State school education in Australia, the US and the UK followed a model of ‘mainstream’ classrooms, i.e. classrooms designed and created for students without disabilities. Alongside these classrooms, often within the same school grounds, were special schools which were designed for anyone with a diagnosed disability that would make learning difficult in a mainstream classroom. Since the 1950s, there has been a gradual shift from special schools to “mainstreaming” or an “integration model” where students with diagnosed disabilities started to become included in mainstream classrooms. In other words, our current ideal of an inclusive school culture started with a disability model.

Within the disability model, educational policy shifted to create an educational environment that aimed to cater to the diverse needs of all students with the idea that students with disabilities should participate fully in regular classes and activities. The idea was based on great values – equal opportunity and social inclusion. Students with disabilities would learn normative social behaviour from students without disabilities, and hence make more friends and be included in the community more once they graduated from school. Students without a disability would learn how to accommodate and make friends with students with disabilities.

Our current model of inclusive mainstream education provides accommodations for students with a diagnosed disability. These accommodations often include an Individual Learning Plan (ILP), teacher in-service training, provision of a teacher’s aide to help the teacher where needed, positive behaviour support plans and strategies.

Some issues with where we are now on our road to inclusive schools.

Reliance on Diagnosis or Identification

We are very supportive of a person knowing that they are neurodivergent and for sharing the knowledge with those who need to know, for example, teaching staff and parents. The advantages are considerable, including greater self-awareness and self-knowledge, leading to greater likelihood of self-fulfilment and well-being. We see labels as being useful signposts – pointing the direction to knowledge that informs self-awareness, self-acceptance, and more effective ways of understanding, relating to and teaching neurodiverse students.

The disadvantages of identification are that many people in our community, and therefore in schools, see autism and ADHD as disabilities and there is a negative stigma associated with the labels. Due to misunderstanding the different social codes of autism and ADHD, they may misread the different ways of relating and communicating as being rude, annoying, oppositional or antisocial. Unfortunately, the high rates of bullying as described below for these students are largely a result of the negative stigma and the lack of understanding that still exist.

The current reliance on being identified in school to receive supports aligns with the medical model of diagnosis to inform treatment. This current system can inadvertently work against a model of inclusive culture because in our current culture both labels are inherently stigmatising and can therefore cause “othering” by both educational staff and students. For example, we have noticed that it has become common in Australian high schools to use the term “autistic” to criticise someone if they make a social mistake, as in, “What is wrong with you? Are you autistic or something?”

An Increase in the Number of Students Needing Accommodations

In the last 30 years we have seen a marked increase in our understanding of the brain and how a different neurology can lead to different ways of learning, communicating, sensing and relating. As a result, ways of being neurodivergent that were historically missed in schools are now being detected more often. These include autism with fluent speech, ADHD, dyslexia, dyscalculia, dyspraxia, certain mental health disorders, attachment disorders, epilepsy, narcolepsy and Tourette’s syndrome. These neurotypes are usually invisible, although they may be clear in certain settings. For example, the Talis Report (OECD, 2019) indicated that 30% of teachers worked in classes where over 10% of students had additional support needs. In the past a teacher may have had 0-2 identified students. As we discuss below, these statistics only cover students who have been formally identified to be neurodivergent.

Teachers are Leaving Teaching

Teachers are leaving the profession in numbers not seen before. For example, in Australia when asked about the likelihood that they’ll leave teaching in the next two years, 54 percent of teachers said they are “somewhat” or “very likely” to do so. (Education Week, 2021). Another survey found that fewer than half (38%) of Australian teachers feel prepared to teach students with additional support needs when they finish their formal training. This is despite 74% having trained to teach in mixed-ability settings as part of their studies (Talis Report, OECD, 2019).

Schools Not Designed for Autistic and ADHD Students

Due to neurodivergence being hidden, undetected and misunderstood the needs of our neurodiverse students have largely been overlooked in the creation of schools. Classroom and playground design and layout, curriculum, teaching methods and school culture have been created to suit the “mainstream student.” Accommodations are made for students that have a diagnosis that qualifies them; however, these accommodations can feel ‘othering’ to the student, and onerous for the teacher.

Poor Outcomes at School for Autistic and ADHD Students

Unfortunately, whilst social inclusion was a goal of inclusive education, bullying at school is a documented consequence and concern. For example, Schroeder and colleagues (2014) found that rates of bullying for children at school were far higher for autistic children with 40% experiencing daily victimisation and 33% experiencing victimisation 2-3 times a week, 73% in total. Zablotsky and colleagues in 2013 asked parents of 1,221 autistic children to monitor bullying over a one-month period. During this period 38% of autistic children were bullied, and a further 28% were frequently bullied (66% in total). Sadly, students with ADHD also experience high rates of bullying and peer rejection.

In our practice over a combined 80 years, we have seen many autistic students suspended or excluded for “behavioural” problems when the problem was lack of understanding or adjustment to the student’s neurodivergent profile.

Nonidentified Autistic and ADHD Students “Fall Through the Cracks”

It is common knowledge now that autistic females, due to masking and camouflaging their autistic and/or ADHD traits, are not identified as being autistic or having ADHD until much later than their male counterparts. Consequently, they are missing out on understanding and accommodations within a system that relies on diagnosis for these commodities. We know that males mask and camouflage too and are also missing out.

In Summary

In summary, six problems with the current model of inclusion described in this article include:

Neurodiversity is equated with disability and needing additional support needs, which increases a sense of “otherness” and being perceived as “less than” for the neurodiverse student and their teachers and peers.

Growing numbers of students in a typical mainstream class are being identified as having additional support needs leading to a sense of overwhelm in teachers.

Increasingly teachers are leaving the profession for reasons associated with being under-equipped and under-recognised for the complexity of the demands of their role, including teaching higher proportions of students with additional support needs.

Schools are not designed for neurodiverse students. They were designed as mainstream schools and adapted for additional support needs rather than for embracing neurodiversity.

Accommodations to mainstream teaching methods are only given to students who receive an eligible diagnosis, excluding many neurodivergent students who mask or fly under the radar such as autistic and ADHD students who mask.

Our neurodiverse students face high rates of bullying, peer rejection and school exclusion in mainstream schools, despite a large rollout of bullying policies, in Australia since the 1990s.

Where to From Here for Inclusive Education for Autistic and ADHD Students?

We believe the advantages of identification of autism and ADHD outweigh the disadvantages, and that schools can create a culture where the advantages of being neurodiverse are accepted, embraced and celebrated. The disadvantages can be managed by creating an inclusive culture that actively addresses and defuses negative stigma and increases understanding and acceptance of neurodiversity.

Fortunately, given the broad acceptance of gender and sexual diversity amongst our young people, we feel optimistic that the students are ready for the change. Armed with new information and attitudes, educational professionals including Policymakers, Teachers, Teachers’ Aides, Principals and Deputy Principals, School Psychologists, Counsellors and Guidance officers, can powerfully change lives by adopting a neurodiversity inclusive culture at school.

The second part of this article will be posted in a month. In Part 2 we share our ideas for next steps in the journey toward truly inclusive and neurodiversity affirming classrooms and schools.

Where to From Here?

If you’re interested in learning more our online courses cover a variety of topics.

References

May 05, 2021 online edition of Education Week as Why Teachers Leave—or Don’t: A Look at the Numbers

OECD (2019), TALIS 2018 Results (Volume I): Teachers and School Leaders as Lifelong Learners, TALIS, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1d0bc92a-en

Schroeder et al (2014) Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders

Zablotsky et al (2013) Journal Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics